How Canadian public sector pension funds profit from global exploitation

A review of Tom Fraser's Invested in Crisis: Public Sector Pensions Against the Future

I’ll admit, when I first heard people studied the political economy of pensions, I wasn’t exactly thrilled. But after studying the financial sector, I realized just how central pension funds are to modern capitalism. If I’d had Tom Fraser’s Invested in Crisis back then, that realization would’ve come much faster.

Fraser’s book tackles a critical question: How did the retirement security of hundreds of thousands of Ontario’s public-sector workers become tied to real estate and infrastructure investments? (4). He focuses on two of Ontario’s largest pension funds, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP).

In 2023, OMERS had a total of $128 billion and OTPP $248 billion respectable, of assets under management. Together, they comprised around $376 billion. To give you an idea of how massive these public funds are, the total value of all private-sector pensions in Canada at the time was around $456 billion. This means OMERS and OTPP were worth around 82% of all private-sector funds. It begs the question, how did this happen? How did we get here? How did these pension funds go from conservative investors in government debt to major players in global finance?

It's exactly this and more that Fraser outlines in his book. He doesn’t just document this shift, he roots it in the broader neoliberal transformations of the 1980s onward. He shows how in Canada, a combination of the public sectorization of the trade union movement, the dismantling of the post-war welfare state, and the financialization of daily life, have collectively produced today’s capitalism in which financialized pension funds dominate our lives.

Blending theoretical frameworks such as Brett Christophers’ Rentier Capitalism, Social Reproduction Theory (SRT), and Marxist geography, Fraser delivers a richly detailed analysis that’s as accessible to newcomers as it is valuable for experts.

social reproduction and pension funds

Fraser's first chapter lays the groundwork for understanding pension fund capitalism by discussing the importance of social reproduction. Social reproduction refers to the processes that are required to reproduce life in general. This encompasses the myriad of labor processes involved in our healthcare, housing, childcare, and other forms of (often gendered) reproductive labor (4).

Fraser's use of SRT allows him to show the interconnections between various circuits of our material reproduction, but inside and outside immediate productive circuits of capital. While much of political economy traditionally focuses on what Marx called the immediate production process, SRT tends to focus on the reproduction of social life in general. SRT helps us to see places of accumulation that aren't captured by traditional viewpoints.

How does Fraser integrate this into the study of pensions? He does so by showing the viewpoints from both circuits, that is, that of capital and of labor-power.

As capitals, pension funds pool workers’ retirement savings and invest them in capital markets to fund future payouts for beneficiaries (4). But as Fraser argues, pension funds cease to be mere financial instruments when paid out. They act as the means through which workers (who are no longer receiving a wage) can access the material necessities of life in a commodified world (14).

Under capitalism, life-sustaining systems like housing have become deeply enmeshed with profit-driven accumulation. The expansion of capital into our everyday lives, in other words, the commodification of our everyday lives, has been a crucial development of the neoliberal period. Neoliberalism has replaced state-backed welfare programs of the post-war compromise with ever-encroaching financialized reproduction.

The commodification of everyday life is crucial for understanding the sources of pension investment profits and the challenges faced by pensioners today. Fraser shows how pension funds, through investing in real estate and infrastructure, feed off the commodification of life’s necessities (11).

These dynamics fuel what he dubs the pension contradiction: the tension between pension funds’ role as profit-driven investors and their obligation to provide worker welfare (12). Financialized pension funds redefine spaces of social reproduction as profit-making frontiers, entering them formally into circuits of capital (13). Capital invests in spaces of reproduction to extract value from commodified life, whether it be, for example, from a private hospital or long-term care home. This value is then used to pay out benefits and fund retirees’ reproduction.

Yet, it's the very sources of profit that are making social reproduction as a whole worse off for both pensioners and non-pensioners alike. This contradiction mirrors capitalism’s core conflict, between the accumulation of value and the needs and desires of people. It's against this theoretical backdrop that Fraser sets the stage for us to understand the full picture of the political economy and politics of pension funds.

origins of Ontario’s pension giants

The book also unpacks the political struggle behind OMERS and OTPP’s transformation. Until the 1980s, Ontario’s public pensions were restricted to low-yield government bonds sold below market rates. That changed with the 1986–87 Task Force on Public Sector Pension Funds, which explored how pensions could "best serve beneficiaries and Ontario’s economy" (30). What’s fascinating is that capitalists, financiers, workers, and unions all agreed reform was needed, though for wildly different reasons (19). Financiers saw untapped profit in private markets (21), workers wanted better returns, and neoliberal policymakers pushed for fiscal responsibility in the name of being fair to taxpayers (33).

The report ultimately concluded that public pension funds would best serve everyone by starting to invest in private capital markets, particularly equities. To financiers and functionaries within the state, the state's supposed reliance on pensions for low-cost financing was framed as a lack of "market discipline" (34). As a result, Fraser frames the final reform as having a dual purpose, boosting capital markets and disciplining the state (35). The ideological belief that markets allocate resources "efficiently" was thus a driving force for change.

Trade unions nonetheless had a complicated relationship with the reforms. Though many were sidelined in the Task Force consultations, they were ultimately supportive of change. As Fraser highlights, many in the trade union movement saw pensions as a new potential source of worker power. Through wielding the ability to decide where to invest funds, workers could potentially acquire a new avenue for collective action outside of strikes and collective bargaining (39).

While there were tensions within the movement itself, many saw the marketization of funds as a means for "emancipation", the gaining of a "freedom" to choose where to invest. But Fraser critiques this as a fatal miscalculation. This conflation of marketization with emancipation was a major fault of the Task Force report and many within the labor movement.

Over the next few decades, financial law would create an ironclad cage from which pension trustees could not exercise meaningful influence (43). Legal practices such as the prudent man principle and fiduciary duty were major barriers against labor's potential pension power. Pension funds are only one example of the myriad ways neoliberalism became very good at insulating capitalism from democracy (45).

the rise of investment in 'alternatives'

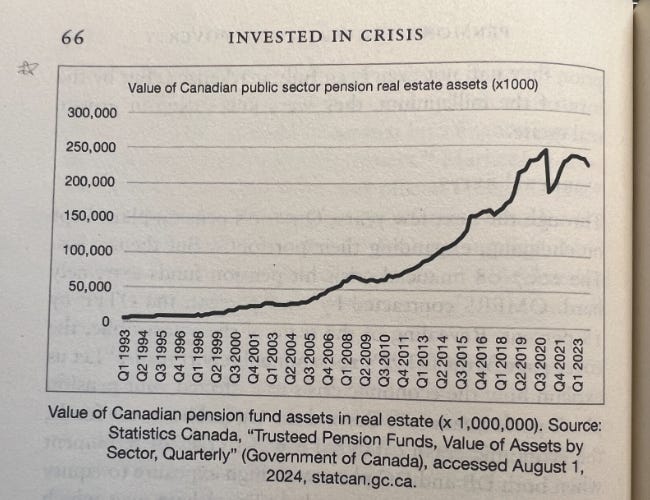

While most pension research focuses on stock markets, Fraser focuses on their ownership of real estate and infrastructure. Real estate started to develop as a global commodity around the same time Ontario pension funds were being reformed. In fact, Fraser shows that the same year as the Task Force, in 1987, the Basel I financial accords determined mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to be AAA assets and incentivized the integration of finance into the real estate sector (64).

Fraser shows how OMERS and OTPP were at the forefront of investment in 'alternative' assets such as real estate and infrastructure. In late 1999, OMERS purchased the entirety of RBC's real estate developer Oxford Properties, which they would fully acquire the following year (64). The OTPP would purchase Cadillac Fairview, a commercial real estate company (64). If you're Canadian you'll immediately recognized that's the name of the various shopping malls all over the country. The answer is yes, the OTPP owned these shopping malls.

What's important to highlight is that OTPP and OMERS are direct ownership of infrastructure. In other words, they aren't invested through an intermediary like an asset manager. This is only possible because of their huge scale, as typically, infrastructure investments are capital intensive (in terms of needed expertise).

Curiously, the 2008 housing and financial crises didn't stop but accelerated investment in real estate. Investment in real estate increased after the crisis. Investors saw "brick and mortar" as more secure (66). The minimization of exposure to equities as a reaction to the crises meant investors sunk more into real estate and infrastructure. This turned them into "core assets" (66) and they were seen as essential to leading "future recovery" (67).

At the same time as residential real estate was booming, infrastructure also became front and center to accumulation. This includes investments in natural resources, healthcare, bridges, roads, ports, airports, energy, and more. This list is not exhaustive.

OMERS and OTPP have huge investments in infrastructure across the globe. As an asset class, infrastructure is the second biggest asset for OMERS and the third for OTPP (80). Again, Fraser highlights how these circuits connect worker's retirement savings to their own urban landscapes and as we'll see, those across the globe (70).

Fraser argues the privatization of infrastructure is part of the continued accumulation by dispossession, the "long durée process of enclosure" in capitalism (78). In this sense, Canadian pension funds have been driving forces in the global enclosure of the commons (79).

pension imperialism

This brings us to another powerful element of Fraser's book, which is the discussion of the international political economy of pension investments. OMERS and OTPP are among the largest investors in global infrastructure, pioneering the direct management of these assets rather than going through a manager (78-9). In fact, most of their investments are international rather than domestic.

Canadian pension funds had $177.481 billion invested in infrastructure as of mid-2022, and $138.137 billion of that is in foreign holdings (95). That means around 78% of their assets are held abroad.

The majority of their international assets, around 77.8%, are held in the U.S. and Western Europe. However, the so-called 'emerging markets' of the global south are growing as a portion of assets. In 2016, OMERS held only 6.3% of its investments in emerging markets, a share that has since doubled over the past decade. Today, OTPP holds 15% in Asia and Latin America, while OMERS holds 13% in Asia and the 'Rest of the World' (95).

Fraser argues that this investment in real estate and infrastructure is part and parcel of the colonial legacy of Canada (93). Canadian pension funds are actively pursuing opportunities to invest in these regions and extract value. In particular, they're always looking for governments interested in privatizing their assets and selling them off to the highest bidder.

For instance, when Jair Bolsonaro was elected in Brazil, Canadian media quickly celebrated the "fresh opportunities for Canadian companies looking to invest in resource-rich countries" (96). Bolsonaro’s administration attempted to sell off Rio de Janeiro’s state-owned water utility, CEDAE, which attracted bids from CPP Investments and AIMCo.

In India, one of the largest emerging markets, Modi has been keen on getting Canadian capital into the country. India's infrastructure deficit has been seen as a major barrier to their replication of China's economic boom. Canadian pension funds have been receptive.

OTPP acquired stakes in the Indian government’s Infrastructure Investment Trust in 2021 and 2022, building on earlier investments in toll roads.

They also purchased a majority stake in Sahyadri Hospitals Group, the largest private hospital chain in Maharashtra, India’s second-most populous state (99). With roughly $3 billion already invested in the country, Canadian pension funds like OTPP are likely to expand their presence further.

mirage of socially conscious investing

While there's a growing calls from within Canada to onshore investments, Fraser points out that the Canadian pension model is essentially international. The goal of the pension funds is to maximize beneficiary returns, not to invest domestically. The point is, the rate of return is the goal, not social outcomes (85).

This speaks to a key part of Fraser's political analysis, which is the critique of 'socially conscious' investing. As the author outlines, there are funds that still believe in the potential progressive social role of their investments. Many believe that ecological stability and profitability are in fact not in opposition, but compatible with one another. In fact, many pension funds are trying to profit from the potential green revolution, looking at getting into the energy revolution from the ground floor (107).

Even the mild attempts at reform, such as ESG initiatives, which are more symbolic than concrete, have been met with massive backlash from the far-right. Fraser thus expresses doubt that it's worth the battle for things that barely work now. In fact, Fraser is blunt about the potential for success of movements which seek to reclaim our social reproduction through financial reform by stating, "There is no space for transformation within the financial system, and efforts to soften the edges function little more than to alleviate political pressure from that system" (112). I have to agree with his assessment.

The pension contradiction can't be resolved with ethical investing practices. This doesn't deal with the contradiction at hand, as Fraser puts it: "The rate of return and social health are directly juxtaposed, there is no harmony between the profit motive and a good society." (112). Unions cannot continue to remain complicit in these practices. While there's been struggles within the pension space, Fraser is clear that bigger and better strategies are needed to resolve our current crises (117).

decommodification or barbarism

Fraser's Invested in Crisis is a fantastic overview for newcomers and experts alike to the dynamics of pension capitalism. In less than 140 pages, the author connects financialization, social reproduction, urban real estate, global infrastructure, and trade unions in a narrative that shows the stakes of our collective political struggle against capitalism. At the book launch, Fraser himself said he didn't know how he felt about the concluding chapter. But frankly, given the size and scope of the book, I think the final message is a strong and important one:

The root cause of the pension contradiction is the commodification of necessities (130).

Yet at the same time, this very contradiction is the business of pension funds to exacerbate:

The Canadian pension system is predicated on a Faustian bargain, that the potentially negative aspects of the investment portfolio are justified by the comfortable retirement afforded to workers who have earned it (114).

Grounding the understanding of pension funds in social reproduction allows Fraser to look at the totality rather than focusing narrowly on the implications for organized labor. This approach is what ultimately makes both the analytical approach and political message of the book so strong.

Fraser avoids the myopic politics that have plagued trade unionism for decades. The connections between workers in the global north and south caused by the investment of pension funds everywhere requires a bigger solution that just mild social democracy. These aren't going to be solved by one local, let alone one union.

The need for an "active politics of decommodification", as Fraser calls it, is more urgent than ever. In fighting toward that end, this book acts as a great resource for convincing supporters and skeptics alike of the need for radical transformation of our social reproduction

References

Fraser, Tom. Invested in Crisis: Public Sector Pensions Against the Future. Between the Lines, 2025. https://btlbooks.com/book/invested-in-crisis

Excellent piece, will definitely be checking out that book for more detail