Race and Capitalism: How Does Capitalism Exploit (and Produce) Differentiated Laborers?

A teaser for future research

The following piece is a script for a presentation I gave last year. It acts as an abridged version of research I began in 2022 on the topic of labor differentiation. The purpose of the research is to show how we can account for labor differentiation within the relations of capitalism outlined by Marx in Capital. In other words, I am seeking to explain how we can account for the production of phenomena such as racialization, gendering, migrant labor, and other processes of ‘differentiation’. It is also comments on broader issues of social theory and method, specifically debates about how we understand the relations between economics, politics and so on (e.g., base and superstructure).

Because this is essentially the script I used for the presentation, it will read as less as a typical post and more as though I was speaking. Changes were made in places which I feel did not express fully my intended arguments. This is a teaser for me posting the more in-depth research, which will come in the following months. Hopefully, it will get people interested in the topic. I hope to show the way I blend Marx’s critique of political economy and contemporary theories of differentiation in capitalism.

Today I’m going to discuss the observed realities of social differentiation between working-class subjects in the capitalist mode of production. Capitalism has shown over the past two centuries that the tendency to produce differentiated workers is all too apparent in its empirical manifestations. The task as those who wish to understand capitalism in order to change it, then becomes to explain in our theory the reason for the appearance of these phenomena. In other words, if capitalist social relations, through their subsumption of our social reproduction, consistently produce differentiated social subjects, how can we explain this theoretically?

To be clear, when I refer to subjectivities going forward, I am referring to concrete social actors and their socially embodied characteristics. This refers to existing concrete social subjects, in body and mind. Furthermore, social difference speaks to how these socio-material forms are articulated in ways that accentuate difference between subjects, particularly in a manner that determines the degree to which they can become victims of class exploitation. In other words, I am trying to answer as Gargi Bhattacharya asks:

“How such fictions of embodied otherness continue to play out in economic formations of a capitalism that seeks to reduce us all to opportunities for value extraction” (2018)

Or as Jason Read asks, how we can have:

“the extraction of wealth from a multitude of subjects that are constituted as basically interchangeable” (2003)

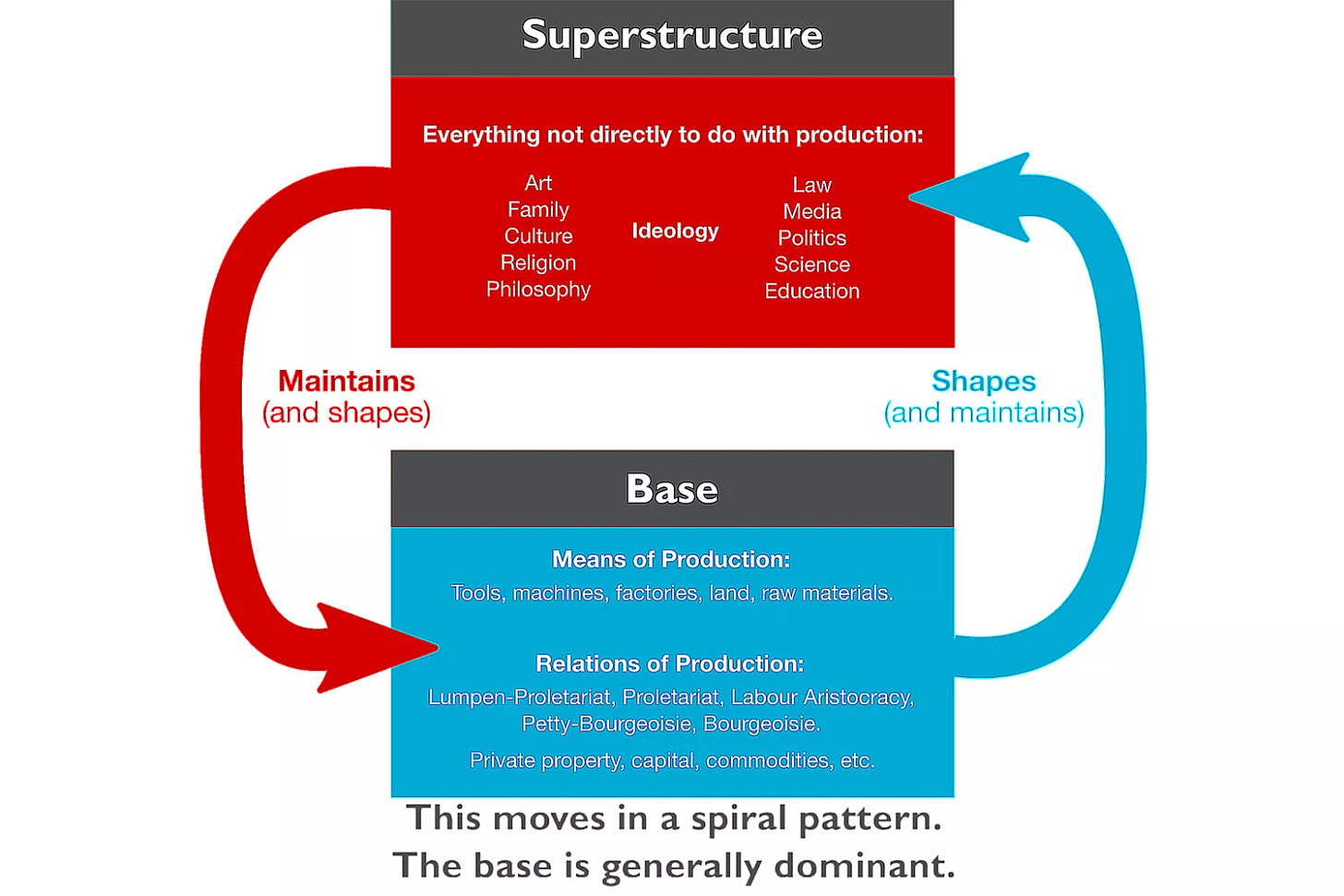

To get at the heart of the issues in theorizing social difference and capitalist production, we need to peer deeper into questions of our mode of production. That’s because many of these issues of understanding labor differentiation allude to deeper questions of our method of scientific inquiry. Specifically, I am referring to the relationship between the so called ‘economic-base’ and ‘political-superstructure’, something that is (often unconsciously) in the background of many of these debates around the centrality of labor differentiation.

As the age-old Marxist story goes, all societies are defined by specific relations of production which mirrors a given stage of material development of the forces of production. This is how Marx outlines it in the A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), and it’s become one of the most canonized and popular pieces of Marx’s theoretical work. The ‘totality’ of these relations is the economic base on which arises the “legal and political superstructure”. This corresponds to a given form of social consciousness, or subjectivity. As Marx outlines:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure. (Marx, A Contribution, 1859)

The base-superstructure metaphor has contained ambiguities which Marxists have debated over for a century. Unfortunately, many have interpreted this in ways which atomizes the ‘economic’ base and presents a unilinear direction of causality in which the base solely determines the political-legal superstructure. The economic thus determines broader social determinations, producing workers subjectivities with little to no feedback coming from ‘superstructural’ elements.

Of course, this unilinear understanding of subjectivity becomes incoherent when attempting to apply it to understanding the social world. All forces of production are the product of a historically specific set of social relations, they are never purely ‘material’ and thus asocial. We can only abstract in our theory from certain contingent elements of social determination to get at transhistorical material determinations, but we cannot ever present a fully ahistorical/asocial set of “material” determinations.

This means subjectivity is never devoid of broader social determinations such as politics. Unless one takes a material-technical view of productive forces, which separates them from all social determinations and presents them as abstractly material and isolated from the rest of the social world, there is no way to separate things into a pure ‘economic’ base as such. The need to theorize economic determinations as political as well is overtly apparent.

Nonetheless, I feel as thought contemporary works of Marxian political economy still steer away from the necessity of developing the abstract determinations of capitalism into more concrete ones. I think a good example is Soren Mau’s popular book Mute Compulsions. In his chapters on “Capitalism and Difference” and “Capital and Racism”, Mau is arguing against the need to theorize differentiation within the abstract logic of capital, that is, its economic-form determinations. While he views things such as gender oppression as “in practice completely entangled” with capital, he does not see it as identifiable within its economic tendencies. Furthermore, Mau rejects any necessity to synthesize the study of social difference in the form of race with capital’s economic determinations (critiquing directly people who do so such as Peter Hudis and Jairus Banaji), stating that the:

“acknowledgment of the deep entanglement of racism and the valorisation of value does not oblige us to locate racism in the core structure of the capitalist mode of production. It is perfectly possible to hold that racism is a social phenomenon which does not originate in the capital form yet is conducive to and reproduced by the latter” (pg 167).

This argument is exactly what I wish to challenge. I think in fact we are obliged to better explain how these processes, that being capitalist exploitation and racialization, work in unison with one another. In a manner, I agree with Mau’s argument. In the most abstract determinations of capitalist production, there is no logical reason for concrete proletariat subjects to be differentiated. But this begs the question, why are we keeping our theory at this level of abstraction? The movement from the abstract essence to concrete appearance, which helps us to parse out the relationship between individual entities, is precisely the point of Marx’s method. We want to get at the concrete manifestations of capital, the more concrete our understanding the more it can help guide our action

In contrast to Mau, I want my theory of capital to give me political prescriptions, that is the point. If not, what am I doing? While Mau attempts to show that these ‘non-economic’ forms are irrelevant for the abstract ‘economic’ determinations of capital, I argue that he ignores how they are immanently related at the concrete level, and that we cannot understand the reproduction of capital without them.

A step to resolving this is better understanding the relationship between ‘economic’ and ‘extra-economic’ factors, that is the political and so on. Returning to Marx’s theorization directly in his three volumes of Capital helps to show why worker’s differentiation is deeply relevant for the economic determinations of capitalism. As Read identifies, the classical metaphor is a limitation to our thinking, as it isolates things into purely ‘economic’ or ‘political’ processes. In my view, it can be detrimental to separate things into economic vs extra-economic in such a rigid form. This doesn’t come close to capturing all the determining factors in worker’s subjectivities today. Instead of looking at how Marx talks about the social totality in the Contribution, Read points to the more consistent comments he makes in Capital V3 in chapter 47 on The Genesis of Capitalist Ground-Rent:

‘The specific economic form in which unpaid surplus labour is pumped out of the direct producers determines the relationship of domination and servitude, as this grows directly out of production itself and reacts back on it in turn as a determinant. On this is based the entire configuration of the economic community arising from the actual relations of production, and hence also its specific political form. It is in each case the direct relationship of the owners of the conditions of production to the immediate producers - a relationship whose particular form naturally corresponds always to a certain level of development of the type and manner of labour, and hence to its social productive power - in which we find the innermost secret, the hidden basis of the entire social edifice, and hence also the political form of the relationship of sovereignty and dependence, in short, the specific form of state in each case. This does not prevent the same economic basis - the same in its major conditions - from displaying endless variations and gradations in its appearance, as the result of innumerable different empirical circumstances, natural conditions, racial relations, historical influences acting from outside, etc., and these can only be understood by analysing these empirically given conditions. [for reference, will not read] (Capital Volume III, page 927)

There’s a noticeable contrast. Here Marx doesn’t separate things into the base and superstructure in the same manner. Marx centers the capitalist (immediate) production process, stating that the economic-form in which surplus labor is pumped out directly corresponds to specific political-forms of domination and servitude. Here we directly see the dialectical relationship between ‘economic’ and ‘extra-economic’ determinations, as political forms “grow directly out of production itself and reacts back on it in turn as a determinant.” The economic determines the political and political the economic. What is highlighted here isn’t a vague economic totality from which the political-legal superstructure arises but one from which it is an immanent property. Furthermore, Marx is clear that the “same economic basis” can contain “endless variations and gradations in its appearance” because of different empirical circumstances, such as “natural conditions, racial relations, historical influences acting from outside”. Thus, we have a malleable model that is clear about centering capitalist production process itself, rather than vague ‘economic’ relations.

But we can go further. We can locate this dialectical relationship between economic-forms and other social factors within the economic categories outlined in Marx’s critique of political economy itself. Not only this, but we can also show, through synthesizing the function of these categories, how capitalist relations generate the production of differentiated workers subjectivities within its core economic structures. Specifically, I look at the process through which the value of labor power is determined.

To start, the necessity of social differentiation for the ‘economic’ relations of capital is immediately apparent in analysing the dual character of commodity producing labor, that is, abstract and concrete labor. Together, these properties of the capitalist laborer are the most basic determinations of their productive subjectivities. Marx identifies two qualities in the commodity, its value and use-value. As products of a specific quantity of abstract social labor, they contain a value. As production of a specific form of concrete labor, they are use-values. The value of a commodity is determined by the socially necessary labor time required to produce it through a socially determined form of concrete labor (keep that in mind).

Thus, as abstract-laborers, workers are homogenized sources of value, but as concrete-laborers, workers are differentiated sources of use-values. The first immediate point to highlight is that workers are presented as the unity of difference and homogeneity. As the social division of labor and commodity production is based on a division between concrete skills, difference is an immanent component of the commodity relation itself. However, this does not yet include the more controversial forms of social difference such as race. To further identify the connection between economic-forms of capital and phenomena of worker’s differentiation, we must analyze the determination of value of the most important commodity to capitalism, labor-power.

One of the fundamental tenants of Marx’s critique is that he sees labor as the source of all value in society. That is why labor power is the most important commodity under capitalism, as it’s only through exploiting it that capital can valorize itself. We already know that capital through subsuming labor to its needs for valorization produced laborers with differentiated skills. But Marx himself says this is not the extent of this differentiation, that there are determinations which are both relevant to economic process but are not reducible to them. That is, he states the value of labor-power contains a moral and historical element to its determination, not merely the technical aspects. This has been highlighted by various authors, in particular Guido Starosta and Alejandro Fitzsimons were an inspiration for my own analysis. I would theorize this further in line with Marx’s comments on the direct political relations within the labor process and argue this continues theorize more concretely the determinations of the capitalist production process.

Thus, from this naturally stems that there’s not only the ‘economic’ differentiation in skills but the tendency towards further forms of social differentiation between different groups of workers. The core structure of labor-power's determination itself makes this a dynamic of the capitalist division of labor. It doesn’t become difficult to see then why there is a drive towards labor differentiation which stems from the economic forms which are immanently related to broader political ones. Within this framing, I argue subjectivities that stem from certain productive relations are products of articulate economic, political, gendered, racial, and other determined relations which are socially embodied by practically working subjects.

Rather than merely focusing on racialization I want to highlight the potential for differentiation based on any discernible social characteristic. This is important, as I want to argue that divisions of labor are social divisions of labor in the general sense, and thus we need to think about the ways in which this differentiation takes place, and it cannot be reduced to skills.

To make these arguments stronger, I want to take it one step further and analyze these relations within another category of Marx’s economic critique. I want to argue that this formal tendency is even more directly linked to capital’s search for surplus, as seen when we further integrate our theorization into capital’s drive towards relative surplus value. Traditionally, when authors focus on Marx’s category of relative surplus value, they focus on its acquisition through the application of scientific methods to increase the real productivity of labor, i.e., lower material costs. While I agree this is a necessary long-run driver of the system, it is not the only means through which capitalists attempt to ‘revolutionize’ its capacity to produce profits.

To show this, let us assume that a capitalist in a specific sector of the division of labor cannot improve further the material-technical features of production, i.e., they cannot change techniques employed to increase labor productivity through the technological revolutionization of the production process. Capital thus can only “revolutionize” and improving the “productivity of labor” by articulating a concrete social form of labor which has a lower value of labor power. In other words, if you cannot increase real productivity, you can lower the formal value of labor power by de-valuing (differentiating) workers.

This is part of how capitalism creates certain productive subjects, i.e., laborers who must produce value for capital. The labor-power of these workers is specifically geared towards creating value for capital. This means it must be reproduced as well to do so, and this means their differentiation is often reproduced as well.

Labor power is very elastic by nature, and thus, the limits of what people can be pushed to accept for their own reproduction is quite variable. Thus, increases in ‘productivity’ through pushing down the value of labor power is in my view the second most common means through which class struggle over productivity takes place, and I would argue in many ways this occurs more often even if it's not anywhere as efficient as real increases in productivity.

In short, I believe there is a systemic tendency to push-down the value of worker’s labor power through articulating forms of social differentiation and linking them to the value of labor power. This takes the concrete form of differentiated labor; in other words, workers are living embodied beings of various socially mediated characteristics, including races, ethnicities, ages, genders, nationalities, backgrounds, languages, abilities, and so on, but are also all subjected to the logic of capital valorization. For this reason, capital can organize the division of labor to its advantage by either officially or unofficially codifying labor differentiation in which they push certain groups of people to perform a specific type of useful labor under particular conditions.

I’m still debating of whether to call this merely a form of ‘absolute’ surplus value, or ‘negative’ relative surplus plus. The reason I believe that absolute does not capture these dynamics is that it speaks to merely an extension of length, whereas relative surplus speaks to an increase in productivity. Now, since productivity cannot be seen merely as a ‘real’ increase in productive capacity but speaks to how productivity is constructed as a category of political struggle, I feel al thought this fits into a ‘regressive’ form of relative surplus value. I take this from Marx’s discussions of “negative” vs “positive” profits.

There’s plenty of examples of how labor comes in highly differentiated forms but is nonetheless a source of abstract value. Temporary migrant workers are not only differentiated through a legal status that makes them more precarious and easily controllable, but they are often highly racialized. Healthcare work is another example where people are often immigrants, racialized and gendered all in ways that effect how we socially ‘value’ this work or justify its lack of valuation.

There’s a sort of fetishism that occurs, in that as divisions of labor shift to eventually change the “type” of subject that is engaged in work, we eventually naturalize it and ignore how it’s a product of conscious (and unconscious) social construction. The subjects in the division of labor however changes. In more concrete terms, the reason a factory owner hires a racialized Mexican worker, a farm owner an “alien” migrant worker, or a middle-class family a gendered/racialized Filipina domestic worker is often because the division of labor has purposely been set up to devalue not only certain kinds of labor, but certain kinds of laborers.

To conclude, differentiation is at the core of the capital relation. Workers are differentiated as concrete laborers but homogenized as sources of value. This is connected further to capitalism drive towards relative surplus value, as the natural elasticity of labor power allows for the scope of devaluation to be a potential outcome of social engineering. Producing a differentiated worker is immanently connected to produce a ‘cheap’ worker. Thus, there’s a systemic tendency to de-value differentiated workers’ labor-power to raise the capacity of capital to make a profit. In short, if we are then to not only teach about the capitalist system, but mobilize those to abolish it, we need to account for these dynamics in our theorizations. This is long overdue.

Works Cited

Mau, Søren. 2022. Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital. London ; Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Bhattacharyya, Gargi. 2018. Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival. Cultural Studies and Marxism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.’

Read, Jason. 2024. The Double Shift: Spinoza and Marx on the Politics of Work. Verso

Read, Jason. 2003. The Micro-Politics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Marx, Karl. 1981. Capital Volume 3: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes and David Fernbach. V. 1: Penguin Classics. London ; New York, N.Y: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

Starosta, Guido, and Alejandro Fitzsimons. 2018. “Rethinking the Determination of the Value of Labor Power.” Review of Radical Political Economics 50 (1): 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613416670968.

Hey man, cool work, especially considering this piece as a preliminary work! I'm planning to cite this on my own blog post, but I don't know how since you don't use your name here. Mind if I ask how to cite this piece? Thanks a lot!

No longer on Twitter - Bluesky only - so wanted to connect. Different from the form analysis you flag, you might nevertheless find grist to the mill in two articles of mine with Andreas Bieler:

1) Is capitalism structurally indifferent to gender? - Environment and Planning A (2021)

2) The dialectical matrix of class,

gender, race - Environment and Planning F (2024).