Jordan the Imperial Vassal: An Analysis of the Jordanian Ruling Class

The politics of class, empire, and settler-colonialism in the Middle East

Jordan: An Imperial Vassal

Since October 7th the world has been shaken by the struggle in Palestine. In response to the genocide in Gaza, social protests have erupted in Jordan. Ongoing for over a week, protestors have called for the closure of the Israeli embassy and end of their peace treaty with the settler state (Middle East Monitor 2024). These struggles mark the greatest pressure the Jordanian ruling class1 has felt for some time, much more than during their own Arab Springs. These events give us the chance to reflect of Jordan’s ruling class and their central but at times precarious role in the region as a node of U.S empire, particularly when it comes to upholding the Zionist occupation.

In many ways, Jordan stands out as one of the most important U.S allies. For starters, the U.S has nearly 3,000 Troops in the country, and U.S aid to Jordan has tripled over the past 15 years. According to a Congressional Research Services report, the total bilateral aid from 1946-2020 was $26.4 billion dollars, with the majority being for ‘economic assistance’ and the rest military assistance (see figures from Sharp 2023). They recently received another 1.6 billion in 2023. To put this into perspective, they are consistently in the top 5 recipients of U.S foreign aid in the region, typically second only to Israel, which received 3.3 billion in aid in 2023.

But why Jordan? Let’s be frank, most Westerners probably know little to nothing about Jordan. Several years ago, when I was in my undergrad, I knew little about it before taking a course on the region and deciding to focus on it for my own research. Knowing much more about Palestine now, it is clearer to me that the nations importance is often overlooked by those who do not know the particular history of Jordan, it’s relation to Palestine and the Zionist colonies, and U.S Empire. As will become clear, much of that ‘economic assistance’ is used to uphold the current configuration of ruling class power and imperial hegemony in the region. Through taking into consideration the history of the Jordanian social formation and its articulation of class relations we can understand it’s centrality to U.S empire and the historical significance of the currently ongoing mass protests and social unrest .

The Hashemite State and Social Formation

Jordan, created by colonial powers after WW1, has a population today of around 10.9 million people and is placed to the East of the Jordan River in Palestine. The population is divided among two main social groups, the tribes that compose the Transjordanians or ‘East Bankers’, and the Palestinian Jordanians (Greenwood 2003).

The first group, the East Bankers, have their roots in the pre-colonial period. At the time, tribal organizations dominated the region of Transjordan including various Bedouin tribes (Jones 2019). Whomever wanted to win the legitimacy of these tribes, needed to be capable mediating conflict between groups by using their wasta. The word is Arabic and means “to connect or bring together”, referring to its original use related to practices of tribal mediation (Jones 2019). Having the right wasta or connections, was critical to building a legitimate support base for a ruler of Transjordanian. Abdullah I had the necessary wasta connections to fulfill this role and become the first Transjordanian king in 1921 (Labadi 2019).

The second group are the Palestinian Jordanians, comprising those who migrated into Jordan over the course of several periods of Zionist colonization and accelerated violence, from the Nakba onwards. Palestinians, despite not being the ‘true’ Jordanians, comprise the majority, being at least 55% of the population (Sharp 2023, 2).

Palestinian Jordanians are important not only because of their relative weight in Jordan’s population. As vassals of U.S empire, the Jordanian ruling class is tasked with containing and subduing the Palestinians who must live right next to their homeland, where many remain and are subjected to a brutal colonial occupation. The U.S is aware of this potential security threat, and it is part of the reason why it has such close allyship with Jordan, as they back their ruling class fiscally and militarily as a reward for containing these refugees and possible resistance fighters by giving them citizenship. As vassals of U.S empire, the Jordanian state and ruling class have an obligation to protect the interests of the U.S, which are the interest of the regional class order. They receive the reward of imperial tributes, all under the conditions that they keep Palestinians in line. However, it will be shown just how precarious this relationship between the state, East-Bankers and Jordanian Palestinians can be at times of tension and growing resistance.

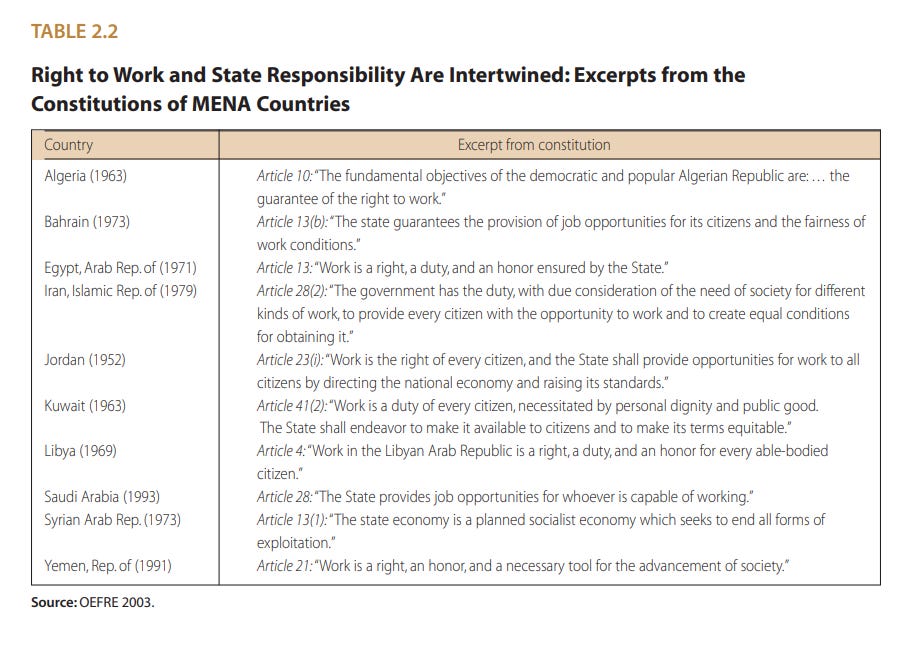

To understand contemporary tensions I’ll start with the specific class-formation which grows in the post-war period. Many MENA nations in the post-war period saw massive expansions of the state in the form of extensive welfare systems (World Bank 2004). These came in response to popular resistance from labor and social groups across the spectrum. The extensive of ‘economic’ rights, often enshrined into state constitution, was seen as a concession by the ruling classes, which still withheld various political rights.2 Below are some examples of the economic rights (for lack of better term) enshrined by the state. This was a region wide phenomena that continues to have relevance today, especially for understanding the Arab Springs. (World Bank 2004, 32)

In Jordan, the ruling class essentialy won favor with the Transjordan population in exchange for guaranteed employment, high subsidies for education, healthcare, gas and food staples. These citizens give the regime legitimacy and political acquiescent (Assaad 2014). Since East-Bankers are the ‘true’ Jordanians, and because of this specific relationship to the formal political ruling class, they are central to legitimacy of the ruling class and thus the stability of the social-formation.

The relationship between the state and ruling class with Palestinians is quite different. While most have been given full citizenship, ethnic Palestinians have never fully integrated into state institutions and have been systematically underrepresented in the public sector, military and parliament. The large and extensive welfare state and its benefits were not extended to the Palestinians in the same way as the East-Bankers. Palestinians have resultingly, dominated the private sector, while traditional Transjordanians have dominated the public sector (Beck and Hüser 2015).

This divide is the crucial element for understanding the social bases of support of the Jordanian ruling class. The ruling class has a broad power-bloc which crosses ethnic lines and the divide between the ‘public-private’ sectors, comprising both Transjordanians in the formal sectors of political power and Palestinian capitalists. The strength of these actors is strongly predicated on their unity and cooperation. For the masses of Palestinians however, there is systemic forms of discrimination in public institutions that have led to long-lasting tensions, and interviews show that Palestinians resent Transjordanian privilege, while Transjordanians still do not fully accept Palestinians as citizens (Jones 2019).

The specific configuration in which state spending on social welfare subdued the East-Banker population was unsustainable, and like many other states across the world and in the region, Jordan suffered from a fiscal crisis (Block 1981, O’Connor 1973). By 1989 the economy needed major restructuring as its debt had reached 259% of it’s GDP (Labadi 2019). This led the monarchy to begin extensive social reforms and reconfigure the economic relations within Jordan itself. Having no other option, the monarchy decided to secure external financing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Jordan was then required to implement structural adjustment policies, including privatizing state assets, devaluing their currency, cutting public spending on government employment and subsidies, all things that would lead to huge domestic backlash (Greenwood 2003). The state tried to alleviate the backlash they knew they would face by two primary means, first acquiring new revenue to sustain some programs and second releasing domestic political pressure by ‘liberalizing’ the political system.

First there are the attempts at restructuring their revenue sources. This brings us to the undeniable imperials character of the Jordanian state and it’s role in sustaining U.S empire. Jordan came the rely even more heavily on external aid to sustain it’s social contract with East-Bankers, and afford to pay for their social services. Particularly following this period the Jordanian state has been referred to in the mainstream literature as a ‘semi-rentier’ state. In traditional international relations literature, especially focused on the Middle East, the ‘rentier state’ refers to those whose revenues are predominantly from sale of a natural resource on external markets, typically oil (Beblawi 1987).3 In the case of Jordan, the state receives ‘rent’ by collecting 1) external aid and 2) remittances from overseas workers in the oil industry, versus a focus on natural resource wealth in traditional rentier states (Brynen 1992). The main form of ‘external aid’ as we saw, comes from the U.S.

What’s important to highlight here is why the Jordanian ruling class receives the high amount of aid that it does. As alluded to above, this imperial tribute is given on the grounds that Jordan assures it can house and subdue the several million Palestinians in their borders. Through assuring that they are not a threat to Zionists colonies to the West, Jordan helps to secure regional stability. They control the border to the West-Bank and help to secure the Zionist occupations capacity to manage Palestinians within their borders. The ‘rent’ Jordan receives is predicated as much on the monarchies capacity to keep their own population in line and their security as it is to providing security for Zionism. This is why the ongoing protests are a major concern for U.S imperialists.

While the economic dynamics of securing revenue are crucial, this leaves out the political determinations of the ruling classes power. Specifically, the following sections will discuss how, in “liberalizing” the political system in response to popular pressures, the state build an institutional configuration which allowed for the consolidation of class power between the various social groups. What this history shows are clear attempts at building a coalition of ruling class power post-1989 by the monarchy and ruling class. The monarchy used strategic electoral design to reduce the opposition pressures in parliament and empower their tribal Transjordanian and Palestinian business supporters. It works as a testament to the ability of states to construct their own internal legitimacy through institutional design.

The Ruling Classes’ ‘Liberalization’

Pressures on the monarchy in 1989 were dealt with directly by 'liberalization’ of the political system. In response to political protests which called for greater democracy, King Husayn announced in July of 1989 that there were would parliamentary elections in November. While this seemed to be a major concession to popular forces, the state believe that the current configuration of electoral law would make these elections work in their favor. The Palace expected that given the organization of electoral ridings and first-past the post system, that the loyalists of the state would be dominate.

In contrast, the results of the 1989 election were a disaster for the Palace. Islamists won a plurality of about 34 out of 80 seats (21 of these were the Muslim Brotherhood) and leftists 14 seats. Essentially, this meant that the political opposition held around 60% of the seats (Greenwood 2003, 255). This opposition in the supposedly representative institution of the people created obstacles for the real functioning of the state as a tool of class and imperial rule. This is because both Islamists and leftists strongly opposes the IMFs structural adjustment program, which would provide a necessary source of funding for the state.

This case reveals the specific character of so called ‘liberal’ democracy. Its modern form has functioned first and foremost as a tool of class power and organization. As is the case in Western liberal democracies, the goal of elections is not about producing real representation or opposition but more about creating a sufficient system for 1) acting as a relief valve, that is, reliving popular pressures and minimizing interruptions to class rule and 2) creating an institutional structure in which differences between members of the ruling class can be sufficiently worked out in order to articulate a hegemonic bloc of political power. Of course, this system is not perfect for the ruling class, as it’s undemocratic and unpopular essence is susceptible to cooptation by popular forces. The experience of the 11th parliament which arose after the initial round of reforms is a case in which the contradiction between necessary functions of class rule and formal but inessential relations of popular representation come into contact.

Nonetheless, this could not stand for the ruling class, as the resistance to the policies necessary for the monarchy to re-establish ‘fiscal’ soundness would hurt the overall legitimacy of the social formation. The experience of the 11th parliament led the monarchy to restructure the electoral system to minimize opposition to liberalization and influence citizens to vote along tribal connections rather than political-ideological lines. New electoral laws were implemented in 1993, and the new electoral regime completely wiped out the dominance of the opposition. They successfully created a 12th parliament comprising a majority of tribally associated independents, followed by business groups, and some political parties (Greenwood 2003).

The new electoral laws clearly favored the traditional East-Banker social base that the state relied on for it’s legitimacy. Not only did the changes to electoral law encourage them to vote, but it also discouraged urban-Palestinians to do so, with estimates of as high as 70% of them absenting (Greenwood 2003, 258). The new electoral system produced a bias towards rural and tribal ties, which negated the potential threat of popular resistance in particular from those more critical of the state, which tend to be Palestinian.

The system was designed in a particular way to isolate the monarchy from the pressures of structural adjustment. It overrepresented tribally associated independents, allowing for the responsibility of ‘rent’ distribution to fall onto these tribal patrons. These parliamentary deputies were now responsible to provide selective access to shrinking public resources, including employment and subsidies to its clients (Jones 2019). The monarch had now shifted the responsibility of citizens welfare onto the elected officials, shielding itself from opposition to economic adjustment, by providing privileged access to state resources to its traditional Transjordanian supporters. Parliament and the Prime Minister were now positioned as those responsible for governmental mismanagement and were treated as the top political institutions by the monarchy (Olimat 2018; Beck and Hüser 2015).

Much of this, however, was political theatre, as not only was the Prime Minister appointed by the king, but the monarchy was the final decision maker on all policy decisions. On paper Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, but ultimate authority remains in the hands of the king. On the other side of the equation the business community that constituted mostly Palestinians, highly benefitted from pro-business liberalization policies and would be a supportive voice in parliament (Beck and Hüser 2015). This parliamentary architecture successfully minimized anti-austerity opposition, optically reduced the monarchies responsibility, and created a parliament were both Transjordanian loyalist and Palestinian business groups dominated. From here, the government was able to balance between the support of these actors to sustain overall social contract stability. The ruling class coalition was placed on a firm institutional foundation, one that would remain for decades to come.

This doesn’t mean relationships were harmonious, as contradictions arose between state support for accumulation vs welfare policies. While the IMF and Palestinian business groups praised the privatization of public assets, the policy received popular rejection from Transjordanians. Seeking compromise, the government promised to run public enterprises to be more efficient and generate profits (Baylouny 2008). The monarchy sold public assets to “strategic investors”, specifically local members of the Transjordanian elite. While this upset many in the business community, this was done as to not give off the image of Palestinian Jordanians buying Transjordanians out of the public sector, something that would have surely led potentially violent political clashes (Beck and Hüser 2015).

Other important measures include deals that secured public sector jobs for several years and limiting the private investors to buying less than controlling shares (Labadi 2019). Compromise was not always attainable, and the government would have to lean on one pillar of support more than another at times. In 1996, due to a $100 increase in the international price of wheat and IMF pressure the government was required to cut food subsides, leading to bread riots. In this scenario, Transjordanians and Palestinians were in complete opposition. Prime Minister al Kabariti fought against populist pressures from parliament, reinforcing the governments commitment to economic liberalization and gaining huge praise from Palestinian business members. Overall, the huge support from the business community was able to offset the popular opposition from the Transjordanians. Where dualism in the labor market has traditionally been a weakness of Arab economies, playing both sides has been a huge part of the Hashemite monarchy’s strategy in implementing liberalizations (Assaad 2014). Going forward, we will see how the state has used the divide between their social basis of support to navigate crises.

The Arab-Springs to Operation Al-Aqsa Flood

The Jordanian Arab Springs and state response reveals much about the articulation of power in the nation as the monarchy displayed similar strategic policy approaches into the 2011 Arab-Springs as they did in early decades. The government first responded to protest by raising public sector salaries and subsidies (Beck and Hüser 2015). However, weak economic growth in the fallout of the 2008 crises made these raises fiscally unsustainable. Since the budget could not sustain this increase, a year later in 2012 the government lifted gas subsides to secure a $2 billion dollar IMF loan, effectively increasing the price of cooking gas by 50% and diesel 25% (Beck and Hüser 2015).

This led to protests, but nothing close to the size, power and militancy of those in other nations such as Egypt or Tunisia, and this is due to the specific class-configuration. The business communities were largely in support of these changes and despite some protested that rose, calls for a fundamental change in the political system were relatively small. The structural benefits incurred by the two bases of support outweighed the benefits of regime change. While Transjordanians were disproportionately those effected by economic liberalization, a majority had privileged connections in the public sector, parliament and military and access to systems of patronage (Assad). Democratization would mean losing their privilege in these spheres, not to mention access to vast networks of patronage (Beck and Hüser 2015).

Conversely, Palestinians understood that engaging in a major resistance campaign would incite violent repression against them. Transjordanian dominance in the military and the pre-existing ethnic tension would have made it easy for the government to justify crushing the protest with force (Beck and Hüser 2015). While the Palestinian population resented their overall mistreatment and discrimination in many societal sectors, they understood that they had overall benefitted from the implementation of pro-business policies, and this outweighed the risky gains of seeking regime change (Beck and Hüser 2015). To fundamentally change the regime and its social contract, many felt, would have led to a lose-lose scenario for both Transjordanians and Palestinian Jordanians. Though imperfect, both groups felt they benefited from the current social formation more than any immediate alternative. Thus, the Jordanian state was able to deal with the period of unrest with relative ease.

Things seem different in the aftermath of Operation Al-Aqsa Flood and the continued genocide of Palestinians, in which over 30,000 have been confirmed killed, but is likely magnitudes greater. The security forces have responded to protests with violent force, and arrested protesters which include politicians, journalists, and union figures, causing them to draw criticism from human rights groups (Salhani 2024). Many have been detained without formal charges and are being held at the Al-Rashid security centre (GCHR 2024). One of the main mechanisms used to suppress people has been the Cybercrime Law of 2023 which allows for charges to be brought against peaceful protesters and imprison them for things they publish on social media, including acts of solidarity with Gaza, and critique of the states’ relations with Israel (GCHR 2023). Some faced charges for inciting others to organize widespread protests and initiate a nationwide general strike.

The Public Security Directorate made a fascistic statement, claiming it “dealt with the participants in the vigils held over the past months with the utmost discipline”. People are supposedly being detained for days, weeks and even months for tweets or retweets, or sharing private stories on Instagram. While the violence helped to lower the number of protests in the early months, now people are coming out in the thousands, leading to intensified oppression.

Although the state is trying to blame covert forces, everyone knows this is an issue that directly involves Palestinians. One researcher at the Arab Center in DC said explicitly “The protests are ongoing because what’s going on in Gaza is very much a Jordanian affair” (Salhani 2024). While there have been protests for the past 6 months, the recent campaign on al-Shifa Hospital and likely invasion of Rafah has brought tensions even higher, with thousands on the streets demanding for suspending normalization with Israel, cancelling trade deals with Israel, and moving away from U.S influence. Boundaries of acceptable resistance are changing, as it’s becoming more common to critique the King, whereas past generations held their tongues more.

It’s easy to see how the state is literally stuck between the classic “rock and a hard place”. On the one hand, the very essence of the social formation and present configuration of the ruling class is based on supporting Israel through economic cooperation but more importantly regional stability by housing Palestinian descendants. Furthermore, it literally could not survive in its current form without U.S aid. These are two sides of the same coin. The government has already requested additional funding, and it’s likely they will get more than requested as is typically the case (see figure from Sharp 2023 below).

While there are pressures, it’s not likely the ruling class will break with imperialist relations now. Of course, they need to seem at least somewhat responsive, and these concerns have been shown by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ayman Sadafi refusing to sign a negotiated water deal with Israel. However, the Jordanian state is as of now, too concrete embedded in the webs of U.S informal imperialism. While the masses are becoming increasingly vigilant and agitated, there is not yet enough turning tides for the state to fall. The ruling class will surely look for ways to appease the masses. In my humble opinion, I think giving their heads on a pike would be a good concession.

Bibliography

Assaad, Ragui. 2014. “The Structure and Evolution of Employment in Jordan.” In The Jordanian Labor Market in the New Millennium, edited by Ragui Assaad, 1–38. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702054.003.0001.

Baylouny, Anne Marie. 2008. “Militarizing Welfare: Neo-Liberalism and Jordanian Policy.” Middle East Journal 62 (2): 277–303.

Beblawi, Hazem. 1987. “The Rentier State in the Arab World.” Arab Studies Quarterly 9 (4): 383–98.

Beck, Martin, and Simone Hüser. 2015. “Jordan and the ‘Arab Spring’: No Challenge, No Change?” Middle East Critique 24 (1): 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2014.996996.

Block, Fred. 1981. “The Fiscal Crisis of the Capitalist State.” Annual Review of Sociology 7: 1–27.

Brynen, Rex. 1992. “Economic Crisis and Post-Rentier Democratization in the Arab World: The Case of Jordan.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 25 (1): 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000842390000192X.

Greenwood, Scott. 2003. “Jordan’s ‘New Bargain:’ The Political Economy of Regime Security.” Middle East Journal 57 (2): 248–68.

Jones, Douglas. 2019. “Talking About Wasta : Attitudes Toward Informal Politics in Jordan.” Confluences Méditerranée N°110 (3): 87. https://doi.org/10.3917/come.110.0087.

Labadi, Taher. 2019. “La Rente, La Dette et La Réforme : Décryptage de La Contestation Sociale En Jordanie:” Confluences Méditerranée N° 110 (3): 55–67. https://doi.org/10.3917/come.110.0055.

Nemchenok, Victor V. 2009. “‘That So Fair a Thing Should Be So Frail:’ The Ford Foundation and the Failure of Rural Development in Iran, 1953-1964.” The Middle East Journal 63 (2): 261–84. https://doi.org/10.3751/62.2.15.

O’Connor, James. 2002. The Fiscal Crisis of the State. New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction.

Olimat, Hmoud S. 2018. “Child Poverty and Youth Unemployment in Jordan.” Poverty & Public Policy 10 (3): 317–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.229.

Salhani, Justin. n.d. “Are Jordan’s Government and pro-Palestinian Protesters Facing Off?” Al Jazeera. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/5/are-jordans-government-and-pro-palestinian-protesters-facing-off.

Sharp, Jeremy M. 2023. “Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations.” Congressional Research Service, June.

“Thousands of Jordanians Protest near Israeli Embassy in Amman in Solidarity with Gaza.” 2024. Middle East Monitor. March 31, 2024. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20240331-thousands-of-jordanians-protest-near-israeli-embassy-in-amman-in-solidarity-with-gaza/.

World Bank. 2004. Unlocking the Employment Potential in the Middle East and North Africa: Toward a New Social Contract. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5678-X.

GCHR. 2024. “Authorities Severely Restrict Public Freedoms.” Gulf Centre for Human Rights (blog). April 5, 2024. https://www.gc4hr.org/authorities-severely-restrict-public-freedoms/.

GCHR. 2024. “Authorities Severely Restrict Public Freedoms.” Gulf Centre for Human Rights (blog). April 5, 2024. https://www.gc4hr.org/authorities-severely-restrict-public-freedoms/.

“Authorities Severely Restrict Public Freedoms in Jordan.” 2024. Global Voices (blog). April 11, 2024. https://globalvoices.org/2024/04/11/authorities-severely-restrict-public-freedoms-in-jordan/.

When I use the term “ruling class” I mean to include both those who are political leaders in formal institutions of state power and capitalists. However, it’s important to note these categories of the “political” and “capitalist” ruling classes are used for analytical clarity and specificity not because they are counter or even mutually exclusive. They can in some cases come in contradiction with one another, as is in the nature of the relative autonomy of state actors from the direct control of the capitalist, who may or may not be organized. As we will see in the case of Jordan, the relationship of the ruling monarchy, East-Bank politicians, and Palestinian business leaders is an interesting case of this form of class power articulation.

This configuration is sometimes called an ‘authoritarian bargain’ for these reason. however, it should not be thought of as imposed from above but rather, fought for from below. This contrasts with the racist image of Arabs as simply victims of authoritarian regimes who need help from the West to find freedom.

There’s much to be said about the problem with the category of rent, as it is often associated with a moralization of the economy actor “not deserving” their revenue because they don’t work for it. There are complexities with how these categories are used, but that is beyond the present scope of this discussion.

Perfectly timed article lol.