This footnote adds to my piece on Marx’s influence on macroeconomics. I allude in it to Input-Output analysis, and the influence that Marx had on Leontief. Here I will discuss this further and add more detail.

Input-Output analysis remains one of the most practically applicable economic models ever developed. It is used by developing nations to calculate various economic aggregates and is a fundamental tool for national accounting systems (see this example from Statistics Canada). It was developed by Soviet-American economist Wassily Leontief to be a quantitative economic model which looks at the inter-industry relationships between inputs and outputs in the economy.

In essence, it looks at how the inputs of one sector become the outputs of another, connecting circuits of goods/service and money to show how they foster economic production/reproduction. Canadian statistician Kishori Lal gives a helpful analogy of how to think about I/O models:

Input-Output tables are like recipe books. Inputs are the ingredients to produce outputs. Like a good chef, one lists the ingredients used by each and every industry to produce output(s). One arranges these recipes in some order so that these can be easily located and the retrieval is efficient.

Leontief’s work was groundbreaking, and he won a Noble Prize for it in 1973. When asked about his main influences, he made the following remarks:

l have no exact idea. There were many of them. When I was young, I studied the theories of the classics of political economy: I count among them Marx, whom I acknowledge as one of the most important economists. The classical works I have in mind, Sismondi and Marx, amongst others. doubtless exercised an influence in the emergence of my input-output analysis. (Clark 1984, 408).

However, earlier in 1966 he in fact stated that the I/O analysis was an “adaptation of neo-classical theory of general equilibirum” (408). This would seem to contradict what he said a few years later. Of course, Leontief’s work is unique, and we cannot reduce it to merely Marx’s. Nonetheless, it’s clear that the analytical content is closer to Marx’s analysis.

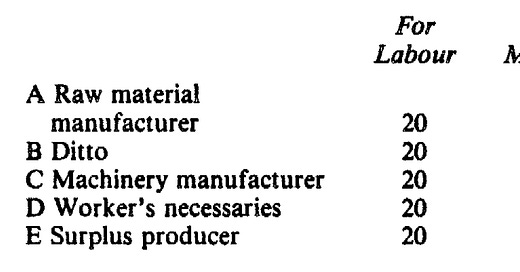

While Marx didn’t use complex matrix algebra, his manuscripts (which later became the Grundrisse) showed he was thinking of economic aggregates along these lines. Building off of Quesnay and the physiocrats, Marx creates a matric of input coefficients and thus is showing he is interested in the interdependencies between these magnitudes.

As Clark states:

He uses the above table to discuss analytically complex problems. By differentiating between product flows and value flows, and by discussing the subsequent impact on actual output proportions if the surplus is spent on increased production instead of luxury items, he is carrying out analysis far from unrelated to the much later work of Leontief” (Clark, 1984, p. 410)

The difference lies more in the sophistication of the techniques used by Leontief than the essential content of the analysis:

“The complexity of the algebra used by both writers is the main difference between their discussions of similar analytical problems. The ease which Marx's model of expanded reproduction can be transposed into a four sector input-output table adds to the argument for Leontief's debts to Marx and puts his acknowledgement of Marx's influence on him in a clearer” (Clark, 1984, p. 410)

Another key point here is that the quantities could be in either monetary or physical terms, showing that Leontief followed Marx in differentiating between flows of products and values. A neoclassical analysis, which has no focus on this aspect of commodities, would be unlikely to produce these conclusions. Other authors such as economist Oskar Lange have also commented on the similarities between their analysis (see Lange in Nemchinov 1964).

Further evidence of how Marx’s commodity analysis is relevant to I/O analysis can be seen in the history of national accounting. The US System of National Accounting (SNA) was developed by both Leontief and Simon Kuznets, a former member of the Jewish Bund group. The way they describe how they got to their model sounds very similar to Marx’s comments regarding the nature of commodities in Volume 1.

As William Jefferies states in his book on Measuring National Income in the Centrally Planned Economies, Kuznets and Leontief argued that commodities as use values are incommensurate (3). In other words, since there is no fixed rate at which use-values exchange with one another, there must be another common element which causes them to exchange with one another.

Neither authors define value and seem to conceal Marx’s definition of the socially necessary labour time required to produce it. As a result, there is no definition of value in their work. But nonetheless, the influence is clear. In fact, even Keynes mentioned Marx’s schema in his notes he used to develop the UK system of accounting but left this out of any published edition.

Works Cited

Clark, D.l. 1984. “Planning and the real origins of input-output analysis.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 14 (4): 408–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472338485390301.

Jefferies, William. 2014. Measuring National Income in the Centrally Planned Economies: Why the West Underestimated the Transition to Capitalism. 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315745350.

Lal, Kishori. n.d. “Input-Output Accounts – The Rectangular Format.” Statistics Canada System of National Accounts.

Nemchinov, V. S. (editor). 1964. The Sse of Mathematics in Economics. First Edition. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

Amazing piece! Reading Samelsons piece from the 1970s and he is surprisingly not as confrontational to Marxian system. Baumol and Avi Cohen were also more supportive.