Marx's ideas left a huge mark on macroeconomics. Noah Smith wouldn't know that.

A reply to Noah Smith

“His theory [Marx] is probably the origin of macroeconomics.” - Lawrence Klein, Noble Prize winning Economist’

“‘It is no exaggeration to say that before Kalecki, Frish and Tinbergen no economist except Marx, had obtained a macro-dynamic model rigorously constructed in a scientific way.’ - Michio Morishima, Sir John Hicks professor at London School of Economics

Noah Smith is an American blogger, economist, political commentator and liberal who writes for his popular blog Noahpinion. Recently, he published a piece commenting on Twitter discourse about whether economists should read Marx. Since the blog was about Marx, I was naturally interest in what Smith had to say. The discourse in question started with various tweets from economists laughing at those expecting them to have read classical political economy, such as the works of Marx and Smith.

Following this came a tweet from English professor Alex Moskowitz, who claimed economics is an unreal discipline because it has no sense of the historicity of its own methods.

I’m not interested in debating Moskowitz points. Instead, I want to look at what Smith says in his rebuttal to Moskowitz about Marx and his relation to modern economics. Smith makes two points that I want to touch on because they allow us to have a broader conversation about scientific theory and Marx’s economic legacy.

First, I’ll push back against Smith’s argument that you don’t need to read the older texts in scientific disciplines. I’ll do so by arguing this assumes scientific development is a linear accumulation of knowledge rather than a competition between various paradigms.

Second, I’ll show despite Smith’s claims that Marx’s theories are irrelevant to modern economics that even elements of mainstream neoclassical economics, specifically macroeconomics, contains ideas nearly identical to those espoused by Marx in Volume 2 of Capital. In the end, I hope to make clear the answer to the question, should you read Karl Marx?

Why you should always learn of the canon

First, Smith states the studying of history of thought isn’t always useful for a discipline because:

Just as doctors usually don’t study the works of Galen, and physicists usually don’t read Isaac Newton, economists don’t really have to read the original works of Alfred Marshall to understand supply and demand, or read John Nash’s original papers to understand game theory. The most useful concepts in science stand alone, divorced from the thought process of their originators. This is why they’re so powerful — anyone can just pick up Newton’s Laws or Nash Equilibrium and just use them to solve real-world problems, without knowing where those tools came from.

I’ve seen this point made online a lot in response to this discourse, with most emphasizing in a similar vein that the reading of older texts is largely superfluous. However, this assumption shows Smith’s weakness as a scientific thinker, let alone economist. What’s my problem with this argument? No, it’s not “I agree with the canon therefore you should read it”. In general, you should at least try and read various schools of thought to judge for yourself which are the most convincing. But this is true for more than just the typical reasons given.

This idea that you need not engage with older texts is predicated on the idea of scientific development being a linear and continuous process in which objective knowledge is accumulated into a cohesive system. Here, scientific progress is portrayed as ‘development-by-accumulation’ and is treated as an asocial process in which the objective development of knowledge occurs without conflict. Thus, there’s a tendency to trust the mainstream because it’s assumed it is hegemonic purely on the basis of its objective rigour.

This understanding of scientific progress was rejected by American philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, who emphasized that all schools of science are based on subjective and arbitrary foundational beliefs. Rather than science being the linear accumulation of knowledge, scientific progress is in practice the competition of paradigms that are often incompatible due to their differing foundational assumptions. As Kuhn summarizes:

“Observation and experience can and must drastically restrict the range of admissible scientific belief, else there would be no science. But they cannot alone determine a particular body of such belief. An apparently arbitrary element, compounded of personal and historical accident, is always a formative ingredient of the beliefs espoused by a given scientific community at a given time” [emphasize added] (Kuhn, 2009, p. 4)

What this means among other things is that scientific knowledge production is inherently social and the subjective element cannot be ignored. This is the case for both natural and social sciences. However, due to the object of analysis being the social world, this is even more so the case with the latter. Despite this, theorists in the social sciences often mask their subjectivity in objectivity, thinking they are being ‘objective’ without realizing subjectivity and objectivity constitute one another. This happens in both mainstream and heterodox schools.

Kuhn’s emphasize on the competition between paradigms is the perfect framework for understanding changes in economic thought.1 The thought of certain authors during the period of classical political economy (CPE) was once the hegemonic paradigm. The emphasize on the production of surplus labor, class revenue, and crisis, among other things, were central to the discussions of these authors. Of course, they didn’t agree on everything, as there were fundamental divides, such as whether ‘demand created its own supply’. Eventually, CPE gave way to neoclassical economics, whose foundation was based more on marginal utility theories of value, among other things.

Did CPE grow out of favour because it was simply incorrect? Of course, it depends on who you ask! Many argue that it was political factors which led to the works of Ricardo and others to fall out of favour, as it was too on the nose so to say about the class nature of capitalism. Others argue neoclassical economics merely turned political economy into a ‘science’, mainly by giving it a rigorous mathematical foundation.

The fact that people disagree on what led to CPE falling to the wayside is precisely the point. If economics merely comprised people in complete agreement, there would be no need to check out other works. Sure, maybe then Smith, Ricardo, Marx, and anyone else wouldn’t be worth your time. But if scientific development is the contestation of various paradigms that argument becomes harder to support. For many, neoclassical economics is the holy grail. In practice, its merely one school of thought based on its own subjective values and foundational concepts, ones which are particularly defensive to liberal capitalism.

Smith’s reference to economics is specifically to the modern mainstream synthesizes of neoclassical economics. However, economics contains various different paradigms and sub-paradigms of “heterodox” schools, including Marxian economics, Post-Keynesian, Institutionalists and so on (for a good introduction into the debate of what constitutes heterodox schools, see Alves and Kvangraven’s work).

For that reason, I always suggest at the very least to pick up a good book which goes through the history of different theoretical concepts, debates and schools in your own discipline. It’s the best way for you to taste test theories. One of the best works of the history of economic thought is E.K Hunt and Mark Lautzenheiser’s History of Economic Thought A Critical Perspective. One of the lessons they take from this history is that when theorists in economics can’t revolve a particular issue theoretically/empirically they tend to revert to their class biases for answers.

Smith is no stranger to these tensions. He arrogantly states that Moskowitz wants economists to read Marx because he likes Marx’s ideas:

Part of the reason, of course, is that Moskowitz personally likes and values Marx’s ideas. He has done research relating Marx’s ideas to those of other leftist philosophers, and he teaches classes on Marx as well. It’s natural that Moskowitz would want economists to study a thinker he likes.

But Smith says this as if he’s any different, as if he doesn’t falls back onto his own political preferences, or as Hunt and Lautzenheiser would say his class biases. Once we admit that there’s a particular subjective side to what constitutes ‘correct’ scientific knowledge, it becomes even more important to check out authors in other schools of thought to test and challenge your own theories. As the following section will hopefully show, Smith assumes his own beliefs to be correct in the abscence of actual knowleged of the history of econonomic thought

In summary, Smith doesn’t see the value in reading classical works because of his understanding of scientific development in economics. If science were linear, if it were merely a matter of accumulated knowledge, then of course according to his standards Marx would be irrelevant. Smith and others would argue well it’s the empirics and facts that determine who is seen as right, but who then determines the correctness of the evidence itself? There’s always politics behind what is seen as correct.

Marx and the Foundations of Macroeconomics

The second claim Smith makes gets more directly his lack of understanding of Marx and his legacy. To counter Moskowitz claim of the lack of historicity in the field, Smith summarizes four articles on neoclassical economics to show “what the economics canon is actually like”. He reviews works by economists Kenneth Arrow, Paul Samuelson, and George Akerlof, to argue that “the ideas of Karl Marx…have mostly fallen by the wayside” and that when it comes to economics, Marx “ultimately [left] little mark on the field’s overall methodology or basic concepts”.

It would be easy to state Smith is referring to mainstream/neoclassical economics and use the above argument to say that Marxian economics is a different paradigm so it’s natural they don’t use the same concepts. That is of course, correct, but I want to go further and argue Marx has left a huge mark on modern economics, particularly through macroeconomics.

Volume 1 of Capital focused on the relationship between labor and capital and is closer to what mainstream economics would call ‘micro’. It focuses mainly on individual economic entities such as the firm (capital) and its employees (labor). The Volume 2 is much closer to what we would call "macro” economics, as it studies the aggregate flows of value across the economy.

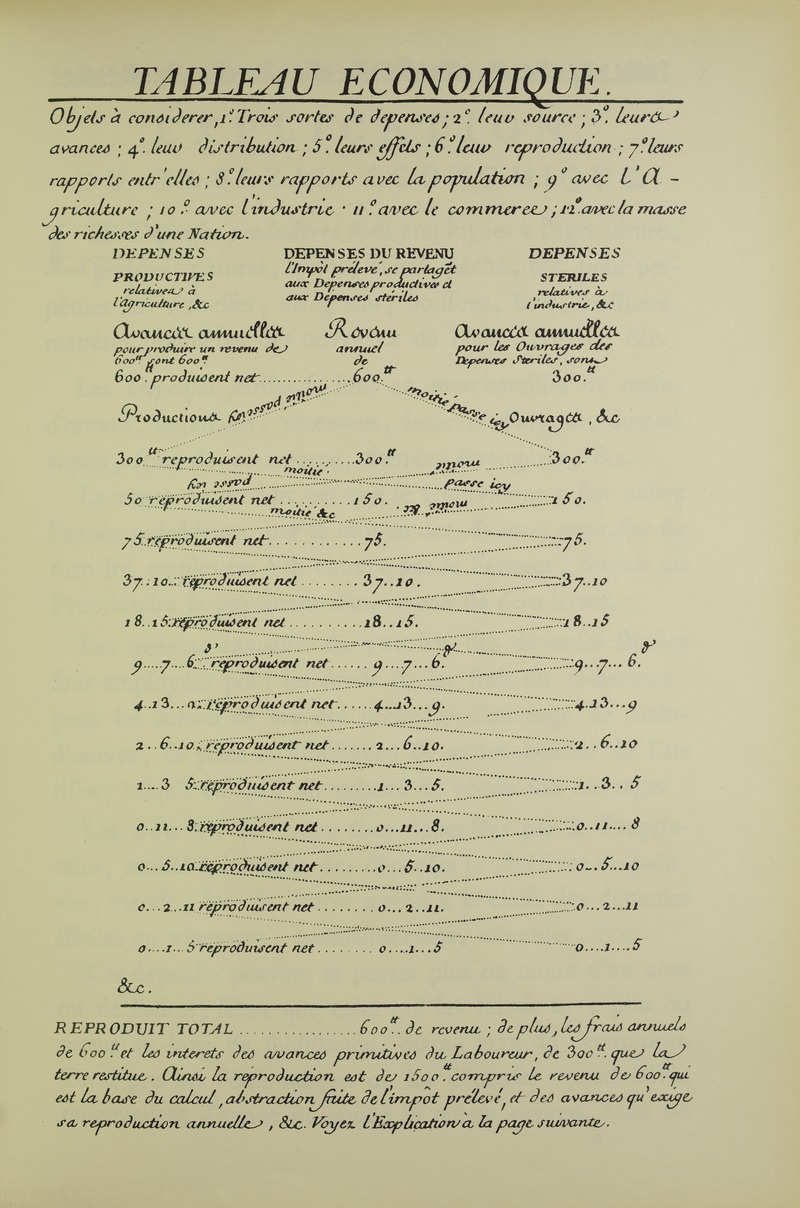

Those who’ve studied economic thought know that an early school of what could be called ‘macro’ economics comes from the physiocrats, a group of French economists led by François Quesnay. They famously argued agricultural surplus was the source of economic surplus value and argued so using their Tableau Économique. Marx was highly influenced by their attempts to map out the distribution of total social value. However, he sided with Smith and Ricardo is stating that labor in general, not merely agricultural labor, produced surplus value.

Building on various authors in the classical school, Marx developed his own understanding of the distribution of value in part three of Volume 2 entitled “The Reproduction and Circulation of the Total Social Capital”. In these pages Marx produces what would become known as his famous schema of reproduction. In essence, this was as system of macroeconomic accounting, a set of variables used to capture the flow of money and goods/services in the economy. What I’ll show is that while the specific concepts used are different the essential relations Marx captures with his economic models are identical to those in contemporary macro accounting.

In Volume 2, Marx analysis the macroeconomy by dividing it into two sectors which he calls ‘departments. The first produces means of production and the second which produces means of consumption (see the formula below). The variables build off the concepts developed in Volume 1 and denote what money is being spent on by the capitalist. In it, c represents constant capital (machines, buildings, materials etc.) and v variables capital (wages). The formulas thus describe total social value as comprised of the sum of spending on means of production + wages + surplus for both sectors, in other words V1 + V2.

Department I Means of Production: c1+v1+s1 = V1

Department II Means of Consumption: c2+v2+s2 = V2

Furthermore, Marx looks at two ways in which the economy can continue, through simple versus expanded reproduction. Simple reproduction denotes a situation in which the economy merely reproduces the current rate of output, while expanded reproduction refers to an increase in output, that is, a situation of growth. Thus, for expanded reproduction, investment must be made in increasing productive capacity. In other words, surplus must be spent on what Marx calls productive consumption (investment) and not merely individual consumption.

So how does this relate to modern economics? Well, what’s amazing about Marx’s schema is that by using them, he comes to many of the same conclusions John Maynard Keynes decades later. In fact, a great introduction to Marx’s schemas is a 1939 essay by Fan-Hung, as it not only outlines the mathematical terms Marx uses but compares them to those used by Keynes.

Let’s look at Keynes equations briefly. For Keynes, aggregate supply price equals total factor cost plus entrepreneurial profit (F +P), and effective demand is equal to consumption plus investment (D= I+C).

F = factor cost

P = entrepreneur’s profit

D = effective demand

C = consumption

I = investment

Despite using different concepts, Marx and Keynes come to several identical conclusions through their own unique accounting identities. Marx’s total product value is identical to Keyne’s aggregate supply price. Keyne’s income is the same as Marx’s total revenue. Keyne’s investment and Marx’s spending on means of production are also the same. Crucially, both see aggregate demand as comprising individual and productive consumption, the spending on wages by workers and on investment by capitalists. As a result, both see the potential for deficiencies in demand and thus problems in realizing profits. I could go even more into detail about the similarities of their ideas, but it would be better not to repeat what others have outlined perfectly. I highly suggest checking out the work of Fan-Hung (in particular there is a list of similarities in pages 123-124).

The point is really to show the continued relevance of Marx’s ideas today. You might argue “well Marx may have had the same ideas but the didn’t catch on like with Keynes” but even that is untrue. Very few people (including economists like Smith) know the line that can be drawn a clear line from Marx to modern day macroeconomics and national accounting practices. Geert Reuten points out in his own analysis of Marx’s schema that:

The Schema also influenced a type of non-Marxian economics of the cycle in the early twentieth century – mainly through the work of Tugan-Baranovsky, the first author to take up the Schema in his own work in 1895 (see also Boumans in this volume). Next, in the 1950s and 1960s the model was of influence for the orthodox economics’ theories of growth and capital mainly through the work of Kalecki.” (Reuten 1999, 197)

I wouldn’t be surprised if many readers haven’t heard of Michał Kalecki, the brilliant Polish Marxian economist. Kalecki was one of the most influential economists of the 20th century. Using the works of Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, Kalecki developed his own theory of macroeconomics and effective demand in his essay An Attempt at the Theory of the Business Cycle. Here’s the kicker, it was published in 1933, a whole three years before Keynes famous The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

Unsurprisingly, by using Marx he came to all of the same conclusions as Keynes. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Listen to the words of Noble Prize-winning Neo-Keynesian macroeconomist Lawrence Klein. Klein stated that Kalecki, who had no formal training in economics and was read up almost exclusively on Marx and Luxemburg, had in his essay:

“created a system that contains everything of importance in the Keynesian system, in addition to other contributions ... [Kalecki] has a theory of employment that is the equal of Keynes’s ... he certainly lacked Keynes’s reputation or ability to draw world-wide attention; hence his achievement is relatively unnoticed.” (Klein 1951, 447-48).

But Klein didn’t merely identify Marx’s influence on Kalecki and ‘heterodox’ schools of thought. He acknowledges outright the importance Marx has had to this field of economic thought in stating:

“His theory is probably the origin of macroeconomics.” (Klein 1947, 118).

Unfortunately for Smith, Lawrence Klein isn’t someone he can just call a lefty commie Marxist and be done with it.2 In fact, his doctoral advisor was non-other than Paul Samuelson, someone Smith himself considers to be part of the canon! Economists like Klein once acknowledged Marx's influence despite disagreeing with him. Today, the discipline is so ignorant of its origins it doesn’t even know basic historical facts about itself.

Smith was right about one thing, that correct scientific concepts stand alone, divorced from the thought of their originators. This is because if scientific analysis is successful in capturing concrete relations, it will be perceptible to everyone engaged in rigorous analysis. That is why despite what Smith says, even mainstream economists are getting a taste of the ideas of Karl Marx! I guess we’re all comrades because of macroeconomics!

I could go on and talk about how Marx’s schema influenced the invention of the groundbreaking input-output analysis developed by Soviet American economist Wassily Leontief. In fact, Leontief himself wrote a piece in The Significance of Marxian Economics for Present Day Economic Theory (included in the edited volume by Horowitz).

I could point to how economist Richard Stone used input-output to develop the national accounting standard used by OECD countries across the world (see Reuten 1999, Clark 1984). But what’s the point? Noah Smith is neither a good faith actor, nor frankly interesting as a thinker.

I’m not arguing that the ideas of Marx and Neo-Keynesians are the exact same, but that should go without saying. The point is to show that anyone who claims Marx’s ideas as a whole are irrelevant is simply ignorant. The similarities between Marx and Keyne’s macro is merely one example of the ways Capital still speaks to the contemporary economic dynamics. It’s part of a list of many examples. But unsurprisingly, Noah Smith wouldn’t know that.

Conclusion: What to make of Marx?

It should be clear that Marx’s theoretical contributions still matter for the discipline of economics. But the question is should you read Marx? Better yet do you need to read Marx? Well, I hope that this small taste of Marx’s lasting legacy on economics at least got you interested in reading Marx.

In practice, I don’t think everyone needs to read Capital I, II, and III cover to cover. But if you’re a thinker interested in the social sciences in general, I think you’re doing yourself a disservice to not at least engage with some of his texts and give them a serious chance. Marx is not right about everything, hell no, but he’s right about a lot of things.

I didn’t write this to convince Smith but to show people who are new to economics/political economy that there are dozens of hubris and ignorant liberals who think because they read some ‘real’ economics and know statistics they aren’t wrong about 90% of the shit they talk about. Smith embodies perfectly the type of person reeking of ignorance and hubris described by Italian-American philosopher Junior Soprano in his cautionary parable:

“Keep thinking you know everything; some people are so far behind in the race they actually believe their leading”

Works Cited

Fan-Hung. 1939. “Keynes and Marx on the Theory of Capital Accumulation, Money and Interest.” The Review of Economic Studies 7 (1): 28–41.

Giovannetti-Singh, Gianamar, and Rory Kent. 2024. “Crises and the History of Science: A Materialist Rehabilitation.” BJHS Themes 9 (January):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/bjt.2024.4.

Horowitz, David, ed. 1968. Marx and modern economics. 1. paperback ed., 4. print. Modern reader 72. New York: Monthly Review Pr.

Hunt, E. K., and Mark Lautzenheiser. 2011. History of Economic Thought: A Critical Perspective. 3rd ed. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe.

Klein, L. R. 1951. “The Life of John Maynard Keynes.” Journal of Political Economy 59 (5): 443–443.

Klein, Lawrence R. 1947. “Theories of Effective Demand and Employment.” Journal of Political Economy 55 (2): 108–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/256484.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1996. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kvangraven, Ingrid Harvold, and Carolina Alves. 2019. “Heterodox Economics as a Positive Project: Revisiting the Debate.” Heterodox Economics as a Positive Project 19 (July):1–24.

Reuten, Geert. 1999. “Knife-Edge Caricature Modelling: The Case of Marx’s Reproduction Schema.” In Models as Mediators, edited by Mary S. Morgan and Margaret Morrison, 1st ed., 197–240. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511660108.009.

It’s important to note that Kuhn’s however rejected the application of his conclusions to the study of social science, in particular the idea that it was general social crises, not just crises in the intellectual space, that led to paradigm shifts. I believe he is laughably incorrect, but that is clear to nearly anyone who is a critical social scientist. For an extensive outlining of the relations between social crises and scientific revolutions, see Giovannetti-Singh and Kent. 2024.

Klein’s intellectual honest is something mainstream economists on twitter sorely lack. In fact, despite being a Neo-Keynsian, his work has been included in an edited volume from 1968 entitled Marx and Modern Economics and pusblished by Monthly Review. In fact, it’s his essay “Theories of Effective Demand and Employment” in which he refers to Marx’s theory as the origin of macroeconomics. I have not read this piece yet fully, other than a few sections for the purposes of this work.

Isn't there some way that you could say that if Marx is still useful, then still, reading the original isn't as useful as reading a new explainer of the original? Like, with Newton, there's obviously better ways of engaging with his ideas than reading the original Principia, like reading modern physics textbooks. Same goes with Turing, Godel, etc. It doesn't seem to me like whoever came up with an idea is necessarily the best at explaining it. Is there a way this is understood differently in economics/sociology generally?

I think the point that economics as a discipline is unaware or unwilling to incorporate its own history (and I can't really comment, my personal experience is too anecdotal for that) is very interesting.

In a sense, Marxist economists like Marx himself, Luxemburg, or even more conciliatory candidates like Bettelheim aren't really part of their discipline, exactly because modern-day economics generally views itself as an "unideological" discipline. Something no Marxist economist I'm aware of ever aspired to. Of course, they only view themselves that way, while reproducing the ideological structure necessary to uphold bourgeois rule.

The mark Marxism left has to be excised in a way, which isn't really necessary for other social sciences.