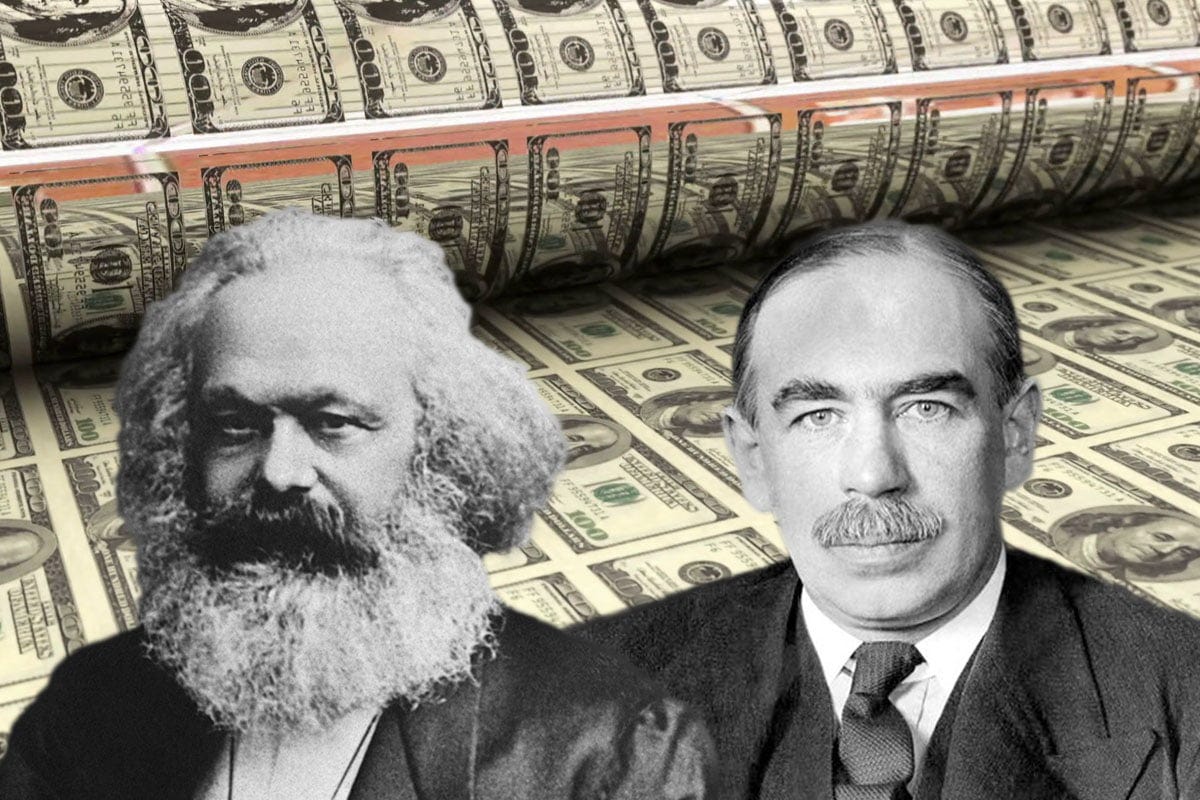

This piece was written before I went on vacation and should be posted just as I’m getting back from it. It’s a little rough and short, but I had these notes from a few weeks ago that I thougth would be really interesting to go over. The contemporary relevance of Marx and Keyne’s critique of restrictive monetary policy frankly could have been written today.

In my post earlier this year on Marx’s relevance for modern economics, I discussed a well-known heterodox economics paper by Fan-Hung entitled “Keynes and Marx on the Theory of Capital Accumulation, Money and Interest”. It’s one of the earliest comparisons of the two economists. It primarily highlights the similarities between Marx’s famous production schemes found in Volume II of Capital and Keyne’s system of macroeconomic accounting found in the General Theory.

They both put forward similar base theories for the systematic defficiencies in demand. For example, the deficiencies of effective demand caused by a decrease in current expenditure on replacement and renewal. Essentially, all else equal, there will likely be a reduction of aggregate purchasing power in the economy that is effected by the need to spend on repairs.

But what I didn’t really discuss was the small yet interesting section in which Fan-Hun points out the similarities between Marx and Keynes’ comments on banking. Both authors had a strong sense of the necessity of monetary expansion both within the private banking system and by central banks, specifically the bank of England. As Fan-Hung points out

“Marx, however, extended the sphere of his research to include a study of money, the rate of interest and financial crises; and one can say that Marx was die first to indiacate the antagonistic relation between industrial profit and the rate of interest, which Mr Keynes has re-examined in his General Theory.…It is of interest in this connection to note how much Mr Keynes' criticism of the Bank Act of 1925 has in common with Marx's criticism of the Act of 1844. (127)

Now I don’t know if the claim regarding Marx being the first to analyze the contradiction between industrial and financial profit is correct (personally I think it’s not). Nevertheless, he goes on to explain that in the early 20th century:

Mr Keynes attacked the 1915 Act which provided that “£120 millions must be held in gold against the active Note Circulation of the Bank Notes and Currency Notes amounting to £387 millions” on the grounds that “the £120 millions must be held (in gold) to satisfy the law is absolutely useless for any other purpose; indeed, it intensified depression through the curtailment of credit in conforming with all the rules of the Gold Standard”. (Fan-Hung 127)

Fan-Hung then points out that Marx had a similar critique of the monetary policies taking place in his day:

Similarly, Marx criticized the 1844 Act which divided the Bank of England into an issue department and a banking department, and provided for a stringent control of the note issue in relation to the gold reserve (127).

Now, Marx’s theory of money and credit more specifically, is one of least well known parts of his work, and quite misunderstood. Some authors such as Geoffrey Ingham argue he simply has a commodity theory of money. While his book on the nature of money is fantastic, I think the (brief) sections on Marx are quite ill informed.

Fan-Hung work provides a small counter to the idea that Marx didn’t see the importance of credit and ‘non-commodity’ money. As Hung points out, Marx himself understood the supply of money “depends on banking legislation and its enforcement.” (133), not merely the autonomous supply of metal by the private sector. He quotes Engels’ synthesizing of Marx’s notes:

…the separation of the Bank into two departments robbed the management of the possibility of disposing freely of its entire available means in critical moments, so that cases might occur in which the banking department might be confronted with bankruptcy, while the issue department still possessed several millions in gold and its entire £14 millions of securities untouched. And this could take place so much more easily, as there is one period in almost every crisis, when heavy exports of gold to foreign countries, which must be covered in the main by the metal reserve of the Bank. But for every five pounds in gold, which then go to foreign countries, the circulation of the home country is deprived of one five pound note, so that the quantity of the currency is reduced precisely at the time when the largest quantity of it is most needed. The Bank Act of 1844 thus directly challenges the commercial world to think betimes of laying up a reserve fund of bank-notes on the eve of crisis; by this artificial intensification of the demand for money accommodation, that is for the means of payment and its simultaneous restriction of the supply, which takes place at the decisive moment, this Bank Act drives the rate of interest to a hitherto unknown height; hence, instead of doing away with crises, the Act rather intensifies it to a point where either the entire commercial world must go to pieces, or the Bank Act. (128)

While Marx did emphasize that gold was the universal equivilant form of value, he certainly didn’t think that money solely came in the form of gold:

All history of modern industry shows that metal would indeed be required only for the balancing of international commerce, whenever its equilibrium is disturbed momentarily, if only national production were properly organized. That the inland market does not need any metal even now is shown by the suspension of cash payments of the so-called national banks, that resort to this expedient whenever extreme cases require it as the sole relief. (Marx, Volume 3, 649)

The critique of both Marx and Keynes of what in essence is arbitrary restrictions on the creation of credit, still rings true today. Whether these restrictions are in the name of keeping an exchange rate with gold or fighting inflation, these both have the effect of falling for the belief that these curtailments will help the economy rather than hurt it. Both have the effect of directly curtailing the creation of money, meaning that if there is a limit to the amount of available money, there will certainly been decreases in output (assuming there are real desires to increase it that match real capacity).

While these two authors are certainly not on the same side of the political spectrum, it's interesting to see how both were railing against the misguided policies of the state, as Hung points out:

For this reason, Marx dismissed the Bank Act of 1844 as the 'crazy' policy of Lord Overstore in much the same way as Mr Keynes stigmatized the Bank Law of 1925 as the sound' policy of Mr Churchill. (128)

Works Cited

Horowitz, David, ed. Marx and modern economics. 1. paperback ed., 4. print. Modern reader 72. New York: Monthly Review Pr, 1968.

Marx, Karl. Capital Volume 3: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes and David Fernbach. V. 1: Penguin Classics. London ; New York, N.Y: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, 1981.